In the time of selfies and the greatest dissemination of images the world has ever seen in its history, excessive consumption has completely trivialized visual manifestations. Once consumed, the images become a pile of useless information that will never be looked at or consulted again. Our generations have learned to look at and discard the image at the same time, without reflecting on it. It’s not their fault, the saturation is so great that while you are looking at one photograph, billions of others are being taken at the same time, and another one is being eliminated at the same time. The field of art is not spared: in 1984 Saturday Evening Post columnist Art Buckwald denounced a challenge already known since Godard’s cinema first showed in Bande à part a silly tradition called “The Six-Minute Louvre” in which travelers fulfilled the inescapable requirement of visiting the three masterpieces of the French museum in the shortest possible time -Mona Lisa, The Victory of Samothrace and The Venus de Milo – by running, and then leaving the museum. There was no intimacy with the work or aesthetic experience, just one more check on the list of requirements fulfilled. The current situation is not far from this nonsense of a visit: a viewer will spend more time engrossed in the digital screen of some device looking at whether the painting was well focused and framed for the photograph. The aesthetic experience has been trivialized and failed. This public will not enjoy that wonderful encounter with some object, building, work of art or artistic manifestation in general that kidnaps our emotions, accelerates the heart and produces a mixture of melancholy, euphoria and tears: the Stendhal syndrome.

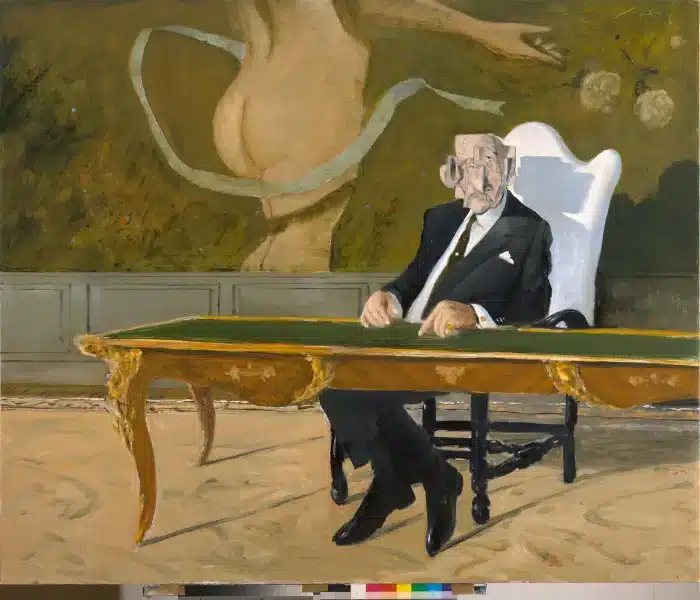

The unfortunate conclusion of this loss of emotion in front of the image is to undervalue it, to lose awareness of all the information it contains, to ignore the physical and intellectual work behind it, and, finally, to assume it simply as something beautiful and well achieved. And it is precisely in that world of immediacy and superficiality of the image where the work of Julio Larraz bursts in to remind us that painting is also an act of tremendous erudition, where even its wonderful aesthetic fact and visual appeal can be equated by its very discourse. A speech that evidences all his intelligence, his training, his concerns and his criticisms. In Larraz’s case, the discourse that addresses his artistic production has taken longer than the execution of a painting, it has taken him a lifetime to create a whole universe that summarizes it and has given a name to that place: Casabianca.

183 x 152 cm

72 x 59 7/8 in

152 x 183 cm

59 7/8 x 72 in

152 x 183 cm

59 7/8 x 72 in

152 x 183 cm

59 7/8 x 72 in

152 x 183 cm

Oil on canvas

76 x 102 cm

29 7/8 x 40 1/8 in

Oil on canvas

Social number: (504)3524065

Physical address: Cr 37 #10a-34

Contact e-mail: [email protected]

Mailing of judicial notifications: [email protected]

© Galería Duque Arango, All rights reserved.